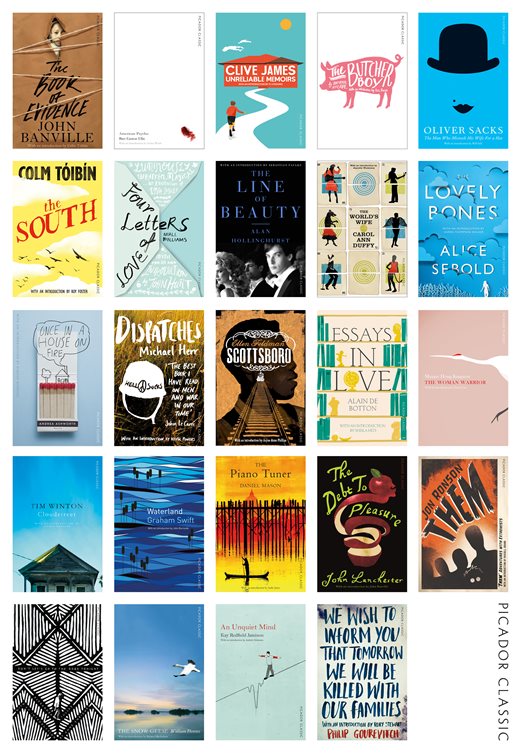

This weekend, I spent a day at the resplendent new Foyles Charing Cross Road attending the ‘Picador Classics Day’; a one-day literary festival to celebrate the launch of Picador’s new ‘Classic’ imprint. It comprises 24 titles, all paperback, a mixture of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, carefully selected with newly commissioned introductions, afterwords and jacket designs. Each title has been chosen because Picador feels it has become, or will become, a definitive ‘classic’ in their publishing catalogue; here is their mission statement:

What defines Picador is the unique nature of each of its authors’ voices. The Picador Classic series highlights some of those great voices and brings neglected classics back into print. New introductions – personal recommendations if you will – from writers and public figures illuminate these works, as well as putting them into a wider context. Many of the Picador Classic editions also include afterwords from their authors which provide insight into the background to their original publication, and how that author identifies with their work years on.

There were a plethora of fine authors on hand to discuss their contributions to the list including John Banville, Carol Ann Duffy, William Fiennes and Alan Hollinghurst. The entire event was chaired by the charming Alex Clark who handled all of the authors with her usual brilliance and panache, keeping them focussed and not allowing them to wander too far into the recesses of memory or self-indulgence (an admirable task in some cases!)

My favourite part of the day was the first event; Canon Fodder: What is a Classic? – a discussion between novelists Philip Hensher, Ross Raisin and Deputy Director of English Pen (and the person behind the newly commissioned intros) Catherine Taylor on what the term ‘classic’ really means when applied to books and what the criteria are. This is a fascinating topic, and one I’m sure everyone has their own view on. For me, as soon as a book is termed ‘classic’ it becomes terrifyingly enlarged and inaccessible in my brain, it takes on a condescending, taunting presence – a kind of ‘read me if you dare’ attitude. I visualise the copy of Ulysses which languishes unread on my shelf, tormenting me with it’s crisp, uncreased pages, its self-satisfied new book glow.

Clark began by suggesting that it’s mostly long, 19th-Century novels that are considered ‘classics’. The exhausted old books that surfaced on your A-level syllabus, the doorstop novels you avoided reading on your BA English Literature course (or if you were me, you stoically read, fuelled by endless cups of coffee, gradually losing the will to live – Dombey and Son anyone? Waverly by Walter Scott?) Philip Hensher alluded to this when he meditated on the fact that a class of perfectly intelligent literature undergraduates in his Exeter University class had found Dickens’ Bleak House entirely ‘unassailable‘; impossible to get through (an anecdote which received an audible murmer of agreement from the audience). So what does the term really mean, and more importantly, what does it mean to us?

Hensher quoted Ezra Pound who described a classic as “a book which has stayed news“. Ross Raisin elaborated by saying it is a book which ‘tackles universal, human themes‘; it may be rooted in a particular time or place, but it has ‘the ability to capture and elevate a moment in history‘ so it becomes much more than the sum of its parts. Raisin attributes this, in no small part, to the use of ‘language which transcends time and place.’ He was very keen to emphasise however that the idea of the classic is subjective, that everyone has their own list of books they consider to be classics. For him, he described them as books which become part of your consciousness, ‘they are inside you, a part of you.’ This could be because you read them at a pivotal moment in your life, or at an influential age, or because they offered a solution or informed a opinion or decision.

Catherine Taylor offered a slightly different slant. She felt that a classic does not have to be a book you instantly love, it can be a book that you take against, that makes you think, debate, and compels you to return to it again and again. She quoted Italo Calvino’s definition; “a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.” She added that classics are books that allow you to bring different experiences to them at different stages of life; they are not age-specific and they continue to give, however many times you re-read them.

Hensher raised the question of why some things survive and continue to be published (sometimes undeservedly so, he felt, mentioning H.E Bates) while others fall out of favour (and out of print) becoming buried in the archives. This is a question I have often asked myself while reading many a between-the-wars female writer, particularly some of the wonderful Virago revivals (Angela Thirkell, Elizabeth Taylor, Barbara Pym for goodness sake!) and Persephone, who specialise in putting these women back in print. How could these wonderful novels ever have fallen out of print? Who allowed this to happen?! Hensher is currently editing a new Penguin Short Story collection and has been seeking out some less obvious choices by searching through library catalogues and looking at the contemporaries of some more famous writers. So far he has found that comedy struggles to stay in print, as does historical fiction, which begs the question – will modern-day ‘classics’ such as Wolf Hall still be read it 50, 100 years time? Hensher thinks not and I am minded to agree with him.

This lively discussion ended with some thought-provoking questions – how do you discover the novels that are worth their salt today? How do you identify the classics that are being published in the here and now? And which novels would feature in each of the panel’s personal canon? Ross Raisin named Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates, Hensher named V.S Naipul. I think Barbara Pym would almost certainly feature on mine, as would A.M. Homes, James Salter, Edward St Aubyn and Zadie Smith. Who would you like to see heralded as a classic author in years to come? Who do you think deserves the status today?

What a wonderful audience to be among and to listen to, and so many great perspectives from the likes of Calvino and others long gone. The notion of a classic does seem to have changed and these collections of newly published titles are a testament to it. I love that different publishers are offering up alternatives and especially the likes of Persephone, turning up the volume on voices that really had been silenced and yet have found a loyal and contemporary audience in the 21st century.

Thanks for your comment Claire. Classics do seem to be a bit more flexible these days and much less excluding and alienating than those scary 19th century tomes! I too love Persephone, i’m so glad that someonw thought to put it right and revive all of these much-loved female writers for a new audience

I think classics from now on will have a very different shape, especially since so many more marginalised groups are participating in and contributing to the discussion and being published. They will continue to change as publishing also begins to embrace a wider demographic of writer. I like to read translated fiction for that very reason that those voices continue to be silent to the English reading world and yet for example here in France, nearly 50% of the fiction read has been translated from another language other than French, they are so much more worldly in their reading and just as likely to pick up a book by a Colombian author on the bookshop display table as they are a French one. “A Colombian author?” I said to my student, thinking, I have never even heard of an author from Colombia!

This was a very interesting post and it sounds like the festival was a lot of fun! To categorize something as a ‘classic’ is always tricky, because there’s no absolute formula for a classic. I often feel slightly apprehensive when people dub something as a modern-day classic shortly after it’s published.

I think one of the reasons why historical fiction doesn’t end up on the “classics list” is because many classics are considered to be so because they reflect and capture the time they were written in. Hence I, too, don’t think that Wolf Hall is going to stand the test of time (although I should probably read it before judging).

Thank you for sharing this!

Thank you for your thoughts, it was a great day and I think i’ll be mulling over the definition of a classic for some time to come. I think you’re right about historical fiction – the point of view and perspective is grounded in the current time, so it will date fairly quickly.

It’s great to read your thoughts and recordings of what was debated at this event. I was really tempted to go to it myself. Very interesting perspectives on what a classic means and, like Claire says, it’s great publishers are challenging the notion of what classics are by publishing books that they believe are classics. Even though the term classic implies they are something fixed I think of it more as a genre whose catalogue of titles do expand and contract over time, but they are books we recognise as saying something important. You’ve reminded me that I really ought to get to reading Barbara Pym. I’ve also never read anything by James Salter. Authors writing today that I’d like to see labeled as classic in the years to come would be Joyce Carol Oates, Nadeem Aslam and Ali Smith.

Thanks Eric, it was a really thought-provoking discussion. I have never read Joyce Carol Oates, but i’d agree with you on Ali Smith – one of the truly great writers of our time. Let me know if you try Pym, i discovered her via the Philip Larkin letters (they were pals and he thought she was seriously underrated as a writer)